Certificates vs. Reality: Why Investors Need Better Metrics

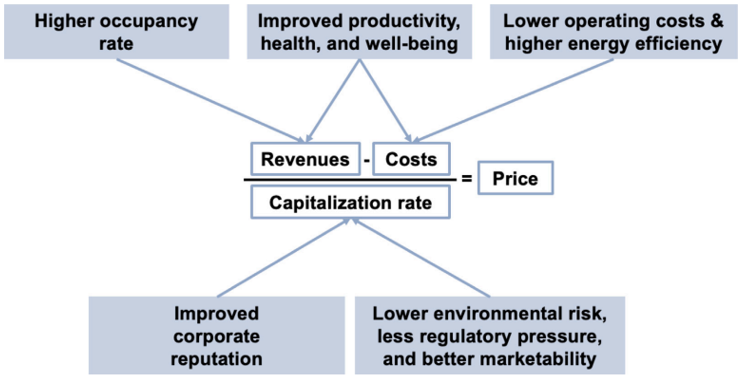

Energy labels and green building certificates are widely used in real estate investment decisions and for good reason: green buildings command higher rents and sell at higher premiums than identical buildings without a green rating (Eicholtz et al. 2010). What matters is not only the certificate itself, but also the information it conveys. Buildings with a green rating tend to possess specific qualities that make them more attractive to tenants and reduce their operating costs. An overview of how these ‘qualities’ materialize is provided in the picture below.

Benefits of green-certified buildings (Flagner et al. 2025)

What do certificates not tell us?

Current labels and certificates effectively convey basic information on building characteristics. For example, if a building holds a LEED or BREEAM certificate, one can assume it meets a minimum standard of energy intensity requirements. If it has a WELL or FitWELL certificate, it demonstrates good indoor quality. However, things become less transparent once we want to disentangle specific metrics, as certificates are based on a wide range of unequally weighted criteria that can vary by assessment scheme, property type, and certificate provider. So, even though we know that a property with a green certificate is supposed to be more sustainable, we cannot tell with certainty what this entails, and what building features drove this rating (LOTUF, 2024). Consequently, it remains difficult for investors to perform a narrower targeting, in which they can focus on those specific buildings with features that really matter to them.

Why transparency is needed.

Without access to the underlying data of these certificates, investors are limited to relying on the certificates themselves when making investment decisions, rather than the underlying data. In principle, this reliance would not pose an issue if the certifications accurately reflected a building’s environmental characteristics. However, because these certifications are based on a broad set of criteria that are weighed unevenly, the level of sustainability they indicate is not always consistent across different certification schemes. Moreover, differences in the assessment criteria of certificates with a similar focus make them hard to compare. An interesting example of this is given by Suzer (2019). The study compares green certificates LEED and BREEAM. Given their shared focus on energy efficiency, they can be considered substitutes for each other. However, when applying the certificate assessment criteria to the same portfolio of buildings, the author finds that LEED and BREEAM scores correlate at only 62%, with LEED scores being significantly higher than BREEAM scores. Another example, where scores without metrics are highly incomparable, is highlighted by APG (2024). When assessing how different commercial vendors assign flood risk scores to the same building, they find a concerning lack of correlation, reducing the value of these assessments, as it is unclear which one to trust.

Implications for investors

Certificates, labels, and scores are commonly used as indicators to cover financial material aspects of climate risks. However, investors should be aware that these indicators are not always reliable. A slight inaccuracy in the indicator could lead investors to overpay for less critical building attributes or receive lower operating benefits than anticipated. If indicators are inaccurate or unreliable, their value diminishes, and they risk obscuring information rather than providing clarity. Instead of relying on proxies, basing investment decisions on the underlying metrics offers the benefits of transparency, comparability, and ease of integration into financial analysis calculations.

Uniform comparable metrics that are industry standards are not yet widely available for investors. To use the available proxies most effectively, further research is necessary. To date, the literature has primarily focused on how different types of certificates materialize. Understanding how similar but distinct certificates and labels interrelate is a crucial next step that enables investors to align investments with their sustainability strategy.

As part of the systemic workstream of GREEN, efforts are directed toward harmonizing climate metrics that are truly financially material. By reducing the complexity of climate data and making these underlying metrics directly accessible, investors can move beyond imperfect proxies and are better equipped to price brown discounts and green premiums consistently and transparently.

Bibliography

- APG (2024) Opening the ‘black-box’ of EU-level flood risk assessments (tech. rep.) INREV.

- Eichholtz, P., Kok, N., & Quigley, J. M. (2010). Doing well by doing good? Green office buildings. American Economic Review, 100(5), 2492-2509.

- Flagner, S., Schiavon, S., Kok, N., Fuerst, F., Licina, D., Loder, A., Rahman, S. A., Scheer, F. A. J. L., Wang, L., Weeldreyer, G., & Pallubinsky, H. (2025). Ten questions concerning the economics of indoor environmental quality in buildings. Building and Environment, 282, 113227.

- LOTUF (2024) Seeing is believing: unlocking the low-carbon real estate market (tech. rep.). Systemiq.

- Suzer, O. (2019). Analyzing the compliance and correlation of LEED and BREEAM by conducting a criteria-based comparative analysis and evaluating dual-certified projects. Building and Environment, 147, 158-170.

Disclaimer

The views presented in this article reflect the views of the GREEN Secretariat but do not necessarily represent those of the individual GREEN members.