How adaptation can preserve property values

Real estate’s fixed characteristics make it less adaptable to environmental threats. Extensive literature shows that real estate markets factor in climate risks, as buyers often seek discounts to offset potential future property damage (Clayton et al. 2021).

At the same time, more brokers and platforms like CoStar and Redfin are providing environmental risk indicators, heightening awareness about climate risks. This trend indicates that the impact on prices will likely grow (Fairweather et al., 2024). Moreover, as climate change continues, extreme weather events are expected to occur more often. Based on the discounting principle, investors will seek higher compensation to mitigate potential damages as these threats become more imminent.

Consequently, without taking adaptive measures, investors may encounter increased discounts, leading to declining property values in residential and commercial real estate susceptible to climate risks. The idea of “absence of adaptation” is significant here, considering that markets are dynamic and will adjust to climate challenges to minimise exposure related value loss. Nevertheless, despite these considerations, adaptability is often neglected in discussions about pricing and investment.

This article examines how adapting to physical risk can minimise losses for property owners. A challenge here is that literature on benefits of property specific developments is scarce. Hence, I highlight literature that documents on area specific adaptation benefits and reflect on what this implies for investment decisions and project specific adaptation opportunities. The article focusses on two studies that analyse the benefits of adaptive measures for residential properties in the Netherlands and the US. Although research in other regions is still limited, broad results are likely generalizable as underlying mechanisms remain the same.

Adaptation can mitigate price effects.

The case of the Netherlands

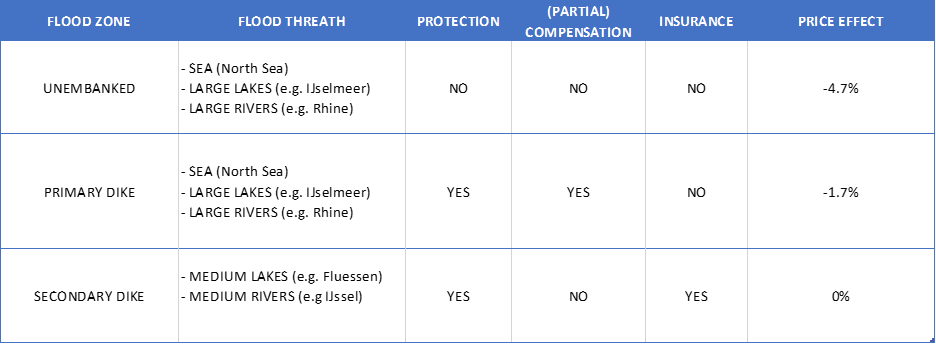

In a recent working paper, Eichholtz et al. (2025) illustrate that flood risk in the Netherlands is generally priced. Nevertheless, areas benefiting from adaptation measures face significantly lower value losses than non-protected counter parts. The table below highlights some of the key results.

The table below illustrates the impact of flood risk exposure on residential property prices in three distinct flood zones. “Unembanked” areas are elevated but lack protection from water barriers, similar to many coastal cities threatened by storm surges and rising sea levels. In contrast to these unembanked areas, “primary dike” and “secondary dike” flood zones benefit from protection through water barriers. We note that homebuyers “demand” discounts of about 5% for being exposed to flood risk in unembanked areas. In the two embanked zones, this discount is approximately 2%, and even 0% for regions with dikes.

Although it is difficult to pinpoint whether the flood barriers or compensation programs are driving the lower flood risk discount, the table adequately illustrates that homebuyers demand significantly less compensation for flood exposure in areas adapted to flood risk. In other words, buyers have more faith in these protected areas and are willing to invest long-term in buying a home despite the high flood risk exposure in such places.

TABLE 1: Flood exposure discounts on residential property prices in the Netherlands (Eichholtz, Kok and Weenink 2025)

The case of the US

In another recent working paper, Bradt and Aldy (2025), explore residential price effects from flood protection infrastructure investments, such as Army Corps of Engineers levees, in the US. Exploiting the actual timing in which these levees were realized they draw causal conclusions that levees increase nearby home values 3 to 4 percent. Notable, the magnitude of benefit is highly similar as in the case above.

The study also observes an interesting side effect. Although levees protect certain properties, they increase exposure for others. This adverse spillover flood risks reduces home values for nearby areas by 1-5 percent.

Implications for Investors

The finding that adaptation can reduce value loss caused by climate threats carries two implications for investors.

First, the studies illustrate that private investors can benefit from public investments in climate adaptation. Therefore, investors should consider whether local governments have implemented proper adaptation strategies when deciding to invest in or divest from a location. Examples of places where adaptation strategies are already in place include Manhattan, Shanghai, and London.

Second, although the examples are based on collective adaptation approaches, they illustrate that adaptive measures are capitalized in property prices. Hence, investors should consider how they can make their own buildings more climate resilient. Interesting adaptation projects can already be observed in practice. An example is the picture shown here, where Dutch pension fund PGGM adapted one of its commercial properties against typhoons and storm surges, by 1. installing a protective wall, 2. building storm barriers and 3. wet proofing the ground floor. While the literature on optimal private adaptation is limited, there are some lessons that we can draw from area wide adaptation projects. An important consideration is economies of scale. Since the costs of water barriers are largely fixed -whether it protects one or many homes- adaptation might be more suitable for commercial real estate or large-scale projects than for stand-alone residential buildings. Moreover, investors should consider price discounts before and after adaptation to determine whether adaptation measures are worthwhile. These can vary based on the level of risk and the realised risk mitigation. If discounts are increasing, adaptation might become increasingly valuable. Last, large-scale projects like levees can alter the risk for properties protected by them, but might also have adverse effects on other properties, that should be considered.

Finally, while few studies focus on building-specific adaptations, some suggest that specific building methods may reduce risks. However, the existing literature is sparse, and how this impacts market values remains unclear. Therefore, the examples of area-wide mitigation mentioned in this article are the most relevant instances of adaptation and market behaviour. Although building-specific adaptations may not achieve the economies of scale that area-wide adaptations can provide, these studies indicate that property adaptations could benefit from additional investments when adaptation is more broadly integrated into the wider area.

Bibliography

- Clayton, Jim, Devaney, Steven, Sayce, Sarah, Van de Wetering, Jorn. 2021. Climate Risk and Real Estate Prices: What Do We Know? The Journal of Portfolio Management 47(10).

- Eichholtz, Piet, Kok, Nils, Weenink, Philibert. 2025. Dutch Dilemma: Housing Prices and Flood Risk Exposure. Working paper Maastricht University.

- Fairweather, Daryl, Kahn, Matthew, Metcalfe, Robers, and Olascoaga, Sebastian (2024). Expecting climate change: A nationwide field experiment in the housing market. National Bureau of Economic Research, w33119.

- Bradt, Jacob, Aldy, Joseph. (2025) Private Benefits from Public Investment in Climate Adaptation and Resilience. National Bureau of Economic Research, w33633.

Disclaimer

The views presented in this article reflect the views of the GREEN Secretariat but do not necessarily represent those of the individual GREEN members.